Envoy says Washington and Islamabad now have a common interest in stopping the Taliban from exporting violence.

Pakistan’s ambassador to the United States, Asad Majeed Khan, says now that the Taliban have seized control of Afghanistan, there is, at last, an opportunity for the United States and Pakistan to work in concert rather than in an atmosphere of suspicion over Islamabad’s alleged support for the Islamist militants. In an interview with Foreign Policy on Tuesday, the career diplomat said he believes there is now a “convergence” of interests among Pakistan, the United States, China, and Russia in preventing the export of terrorism. Khan also contended that, contrary to reports of Taliban brutality and atrocities, the Taliban “seem to be listening to the counsel of the international community.”

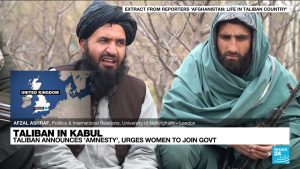

At a news conference in Kabul later Tuesday, a Taliban spokesperson said the militant group would pardon anyone who had resisted it, and “the future government will be inclusive.”

“We do not want to have any problem with the international community,” said the spokesperson, Zabihullah Mujahid. Despite intelligence reports that the Taliban continue to harbor al Qaeda, he added “we are not going to allow our territory to be used against anybody, any country in the world.” He also said women would be allowed to work and study and will be “very active in the society but within the frameworks of Islam.”

This interview with the Pakistani ambassador has been edited for length and clarity.

You can support Foreign Policy by becoming a subscriber.

Foreign Policy: Pakistani Prime Minister Imran Khan said on Monday the Taliban takeover meant Afghans had broken “the shackles of slavery.” What did he mean by that?

Asad Majeed Khan: There is a lot of that appearing in the social media space, and sometimes, these things are quoted out of context, so I have not really seen the context in which what has been attributed to the prime minister have been said. I would recommend to you the statement that the [Pakistan] National Security Committee issued after it met Monday. That fairly and comprehensively articulates Pakistan’s position. [The statement said Pakistan is “committed to an inclusive political settlement” and “the principle of non-interference in Afghanistan must be adhered to.”]

FP: Did the prime minister not make that comment about slavery?

AK: It’s really hard to keep track. There’s so much out there in the social media space.

FP: Let me put it more broadly. There was some cheering at high levels in Pakistan over the Taliban victory. On Sunday, the minister for climate, Zartaj Gul Wazir, tweeted that the collapse of the civilian government in Kabul was “an appropriate gift for India on its Independence Day.” It’s clear that positing the Taliban as a hedge against Indian influence in Afghanistan has long been part of Pakistan’s strategic policy.

AK: Really, if you were to put aside whatever these isolated statements are, obviously people … may have different takes as individuals. We are a free and democratic country, and there are a whole range of views for and against the policies of the government. But I think what is really important is to see where we have consistently stood over the past few years. I’ve been part of these conversations almost directly for more than 12 years, and I can say that we have covered a lot of ground in terms of addressing U.S. concerns on safe havens in Pakistan, and we are going all the way to cleanse those, addressing concerns on cross border movement and then doing whatever we could to bring the Taliban to the negotiating table. And we did it simply because we see that a continuing conflict in Afghanistan works to our utter detriment. It is against our interests completely.

FP: OK. Whatever the past issues of support by the ISI [Pakistan’s intelligence service] and Pakistani military—all that may not be as necessary now that the Taliban have taken control of Kabul. So what are your concerns going forward?

AK: It’s very important to basically go back because what we have seen or what we are seeing in Afghanistan is an eye-opener. It clearly brings out the fact that unfortunately, Pakistan has long been for the Afghan government an afterthought and excuse and a diversion to cover up for their deficiencies. Unfortunately, it suited the political convenience of the United States also. … We have supported the peace process completely, and we will continue to do that.

FP: Do you deny that, at least in the past, there has been support by the Pakistani ISI and military for the Taliban movement?

AK: It depends on what you mean by support, and does it imply—

FP: Everything from providing safe harbor to their leaders and their families to supplying logistical support to their military and hospitalization for wounded Taliban militants.

AK: Pakistan has been a safe harbor, but is there a distinction between Afghans and the Taliban? We have been a safe harbor and safe haven for all Afghans. And today also, if anything goes wrong, Pakistan will be the destination of choice again. So what can we do about that? And they don’t necessarily carry signs of who they are. So far as the Taliban’s military successes are concerned, what they have done in the field is something we have nothing to do with. We have basically stood by our commitment not to let our territory be used. There are these tribal areas that have been presented as safe havens, and for the past four years at least, we have completely cleansed them, integrated those areas into mainstream Pakistan. We have built a fence, you know.

FP: So there is currently no Pakistani support whatsoever for the Taliban takeover?

AK: Absolutely not.

FP: Obviously some U.S. officials believe there is.

AK: The point is their assessments have largely been proven wrong, and I think that right now, this is not the time to point fingers. … It’s not that the Taliban were on our payrolls.

FP: Is all the Taliban leadership out of Pakistan?

AK: I only know the leadership has moved from Doha to Afghanistan.

FP: So what are Pakistan’s main sources of concern right now?

AK: We would like to see an inclusive government, and that was something we hoped would come out of an inclusive peace process. These developments have clearly been a setback. So we are doing whatever we can, and the extended “troika” [the United States, Pakistan, China, and Russia] had a good meeting in Doha on Aug. 10 and Aug. 11. We are engaged with these key players to have all the ethnicities of Afghanistan represented. The diversity of Afghanistan also needs to be reflected in the composition of the government.

FP: What hopes do you have for achieving that? What kind of influence does Pakistan have now? This seems an even more extensive Taliban takeover than in the 1990s, since the anti-Taliban militias just folded. The Taliban are in total control.

AK: What we are hearing from the ground and what we are seeing in terms of developments is the Taliban seem to be listening to the counsel of the international community. There haven’t been very many violent incidents. Some schools have been opened. One of their leaders was interviewed by a female anchor.

FP: But there are many reports of brutality on the ground, women and girls taken from schools, mass killings, and then the heart-wrenching scenes of Afghan evacuees crowding into the airport. There seems to be quite a difference between what the Taliban leaders in Doha were saying and what’s happening in Afghanistan.

AK: I think they should be concerned because the international community is watching and they will be judging them based on what happens on the ground. … They have been in control of large parts of Afghanistan already for quite some time, and the reports we are getting is they are mostly conducting themselves responsibly. Despite some incidents a few weeks back, it’s been very smooth. … They are basically talking to everybody. Our embassy is open and working around the clock. We are doing what we can to facilitate the repatriation of nongovernmental organizations, journalists, and others. Many evacuations are taking place through Pakistan.

FP: Does this takeover clear the air in some ways between Islamabad and Washington? Obviously this issue of covert Pakistani support of the Taliban has been hanging over the relationship for a long time. Is there a way forward now?

AK: That’s the question we are grappling with because, frankly, our relationship with the United States has been defined and deeply influenced by Afghanistan. It’s been seen through the Afghan prism all these years. … So we are working toward moving onto another relationship. Despite all the challenges today, the United States is still the largest export destination for Pakistan. It is the third largest remittance sender to Pakistan. The United States has also been one of the top five investor countries in Pakistan.

FP: What are the concerns of your government now about extremist Islamist ideology spreading back across the border? After all, attacks by the TTP [Tehrik-i-Taliban Pakistan] have reportedly increased in recent months within Pakistan.

AK: There are two levels the TTP has been a concern and still is because when we cleared our areas, they found safe havens on the other side. And that’s a concern, and that is our expectation also: Afghan territory will not be used against us. Whoever will be in control must not let it be used. Having said that, I think the fear of extremism and sometimes the way it is going to impact Pakistan is exaggerated in the think tank space inside the Beltway. Because if you look at Pakistan, frankly all the mainstream political parties are more to the center or slightly to the right of center. And so-called fringe religious parties do not have that huge a following given the character of our society—we are religious, but at the same time, we believe in embracing a pluralistic Islam.

FP: But will there be more attacks from the extremists?

AK: It’s not about the Taliban. And that’s why we’ve been investing so much in the peace process. Our view is that even for the United States, the best counterterrorism investment is to invest in peace. If you don’t have peace, you have ungoverned spaces. Then you have militias and countries hedging their bets. We’ve seen that play out in the past, and we don’t want that repeated. So the best way to counter extremism is to have a government that is under control … ready to work with the international community.

FP: Have there been conversations between Islamabad and Washington in the last few days?

AK: Secretary [of State Antony] Blinken spoke to the [Pakistani] foreign minister, and this was quite lengthy. Really I think the good thing today is that regarding Afghanistan, there is a complete convergence between the United States and Pakistan. You want the parties to get to a common understanding. We want that. You want the violence reduced. We want that. You want the gains of the past preserved. We want that. … China and Russia are concerned too [about terrorism]. We are all worried.

FP: Are there any initiatives coming? For example, we know Pakistan wants no U.S. military presence within its borders, but will Islamabad help on intelligence and other things to support the U.S. posture of maintaining over-the-horizon vigilance against al Qaeda, the Islamic State, and other terrorists?

AK: It’s developed so fast. It’s been happening on an hourly basis. The bottom line is terrorism is our concern as much as it is your concern. And there are ways in which we can and will cooperate with the international community and the United States. We have cooperated in the past.

FP: You’re facing a sometimes aggressive India under Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi. Do you see the new Taliban-run Afghanistan as an ally against India?

AK: Unfortunately, Afghan territory has been used against us. Even this so-called Sanction Pakistan campaign—basically, a lot of it originated from India. It’s sad. … So therefore, Afghanistan will have to sort this one out. India has closed its embassy there. … We have made overtures for engagement, but Prime Minister Modi, the problem really is that his politics somehow puts Pakistan in the domestic political scene and context and … it suits him to maintain a hard line on Pakistan, and that’s what he’s continuing to do. And Kashmir is another place where he has taken a unilateral action. … So Modi is not conceding anything, and the stalemate continues.

FP: What do you think China’s relationship will be with Afghanistan? Here we are in another version of the so-called Great Game, where the great powers vie for influence on the world stage using Afghanistan as a platform. In Southeast Asia, we are dealing with an aggressive Chinese presence against Taiwan—and more broadly, a test of the overarching rivalry between the United States and China. Will China see the U.S. abandonment of Afghanistan as a signal that Taiwan is vulnerable too?

AK: Honestly, I think happily, Afghanistan is a convergence [of interests], and the extended troika … indicates the concerns are common.

FP: Shouldn’t these concerns be common? China has its concerns about Islamist insurgents, and Russia has its own worries about the Islamist Chechens. All the big powers fear Islamist extremists.

AK: Everybody. That’s the huge base to work from for peace in Afghanistan. We have always maintained that Afghanistan should be an arena for cooperation rather than a place for confrontation.